The REAL Skandalkonzert!

March 31, 1913 — Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg and Anton Webern

An Exploration of Myth versus Reality and the Importance of Primary Sources in Reporting on Historical Events

First, the Mythical Riot — Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring

In our “Music of the Twentieth Century” history class, we have discussed the common myths regarding a supposed riot at the premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring on May 29th, 1913, at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris. As Thomas Forrest Kelly describes in his book, First Nights: Five Musical Premieres (2000), there were many conflicting reports of the audience response to the Rite of Spring premiere. Kelly states that Jean Cocteau, a French poet and critic in attendance, noted that the audience “laughed, scoffed, whistled, cat-called” (p. 292). Reports of the lights having to be turned up during the actual performance due to the vocal uproar or the police intervening have never been veritably and consistently corroborated.

One thing is for certain… the show went on and the full performance was completed. There was no physical riot, no interruption of the concert performance. There may have been a lot of hootin’ and hollerin’ but there certainly was not a riot. In fact, Kelly goes on to say, “At the close of the thirty-four-minute ballet, applause as well as shouting broke out. Indeed, there were four or five curtain calls — including a well-deserved one for Monteux and his band — before the evening continued.” (p. 293).

Receiving curtain calls is pretty impressive for a performance that was purported to have been disdained. Audience members are not going to continue clapping unless they either enjoyed the performance, or in the case of the Rite of Spring, recognized the work as a ground-breaking moment in musical history.

Now, here’s The REAL Skandalkonzert!

I find it interesting that Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring has had the curse of so many inaccurate myths surrounding the premiere yet there is another composer’s concert which is rarely mentioned that DID involve shouting and protests, the throwing of punches, an interrupted performance and the calling of the police with the arrests of some in attendance.

When did this occur, you ask? Well, actually two months before the premiere of the Rite of Spring. The Skandalkonzert, the name that has been attributed to this particular performance, was an event that took place on March 31, 1913 in Vienna at the Musikverein venue. In her article, “Noise and Arnold Schoenberg’s 1913 Scandal Concert”, Joy Calico describes the “Portrait of the Composer” concert featuring Arnold Schoenberg’s works along with premieres of compositions by Schoenberg’s students: Alban Berg and Anton Webern. Please take a journey with me as we explore the happenings at this Skandelkonzert.

The Concert Program Bulletin — March 31, 1913

As you can see, this performance featured Schoenberg’s, Berg’s and Webern’s compositions with some Zemlinsky and Mahler thrown in… well, the concert never made it to the performance of Mahler’s piece.

What was the offending composition??

Alban Berg’s “Fünf Orchesterlieder nach Ansichtskarten von Peter Altenberg”

Joy Calico states in her article on the Skandalkonzert:

“The details reported in the press vary from one account to another, but all agree that some portion of the audience abandoned all decorum after Berg’s third Altenberg Lied, in hindsight fittingly titled ‘Über die Grenzen des All.’” (p. 29)

“Über die Grenzen des All”, in German to English translation websites, translates to “Beyond the limits of space” (or universe).

The 3rd lied, “Über die Grenzen des Alls”, begins at the timestamp, 3:58, and starts off with a full 12 tone chord! I imagine this chord probably did sound “beyond the limits of space” and not of this world (to the tonal ears of that era). Perhaps the audience had heard enough atonality, precipitating the audience’s raucous behavior?

Take a listen of the 3rd lied at the timestamp, 3:58:

What happened next??

Andrew Barker in his chapter in the Cambridge Companion Online, entitled “Battles of the mind: Berg and the cultural politics of’ Vienna 1900”, describes the commotion at the concert so very well:

“On the evening of 31 March 1913 the Great Hall of the Vienna Musikverein erupted as Arnold Schoenberg conducted two of Berg’s songs Op. 4, the Funf Orchesterlieder nach Ansichtskartentexten von Peter Altenberg. The audience bawled for composer and poet to be sent to the madhouse, knowing full well that Altenberg was already a patient in the State Mental Institution at Steinhof on the outskirts of the city. Fights broke out, the police were called, and Erhard Buschbeck, a friend of Berg’s and an organiser of the concert, was arrested after trading blows with the operetta composer Oscar Straus. At the trial Straus remarked that the thud of the punch had been the most harmonious thing in the whole concert.” (p. 24)

(Oscar Straus’ sense of humor is interesting!)

So, unlike Stravinsky’s premiere of the Rite of Spring which is frequently said to have had a “riot”, Schoenberg’s concert truly did have a major protest, physical altercations, the arrival of the police with arrests and an abrupt end to the evening’s performance.

In her article on the Skandalkonzert, Calico adds more juicy tidbits:

“By some accounts Webern antagonized the crowd by bellowing “Hinaus mit der Bagage!” Dr. Leinweber, the police officer on duty, was unable to restore order, and Buschbeck took the stage in an attempt to settle the crowd before Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder began, asking the audience to either listen to the final piece with appropriate respect or leave the hall. One Dr. Viktor Albert was said to have called Buschbeck a “Lausbube,” whereupon the young impresario allegedly leapt into the crowd and struck him in the face. The melee was on. The concertmaster announced that the orchestra could not play Mahler under such conditions, the musicians left the stage, and the house lights were turned off in an effort to clear the hall; eventually, the audience dispersed.” (p. 31).

(“Hinaus mit der Bagage!”… literally, “Out with the baggage!”; “Lausbube” translates to “rascal”)

Schoenberg’s view on the Skandalkonzert (an interview)

The day after the tumultuous concert, a correspondent from Die Zeit newspaper met with Schoenberg to discuss the event. This is one of Schoenberg’s responses:

Moral of the story…

There a few lessons we can learn from Schoenberg’s Skandalkonzert as well as the premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring:

First, as is the case with the myths surrounding the Rite of Spring premiere, it is extremely important to explore and utilize primary sources to understand the truth of a matter. Primary sources such as contemporaneous concert reviews, interviews and personal writings can help to clarify history and report history accurately to future generations. There are still scholarly sources which generalize a “riot” at the premiere of the Rite of Spring… but that general term is misleading and really, not quite accurate.

Most intriguing, is the glossing over of Schoenberg’s Skandalkonzert in the annals of music history. The Rite of Spring always wins the prize in discussions of 20th century music that prompted outrage and protest within the audience. But in my humble opinion, the outrage was much more intense at Schoenberg’s concert of March 31, 1913.

I wonder why this event is not quite as well known as the Rite of Spring premiere?

Lastly, it’s clear that not everyone is going to like “new” music. The sounds of atonality and dissonance were foreign to audiences at the turn of the 20th century. I believe that these unfamiliar sounds contributed to the audiences’ responses. Certainly, there were other societal factors at play as well such as societal status and cultural affiliations… but that’s another blog post!

On that note (pun intended!)…

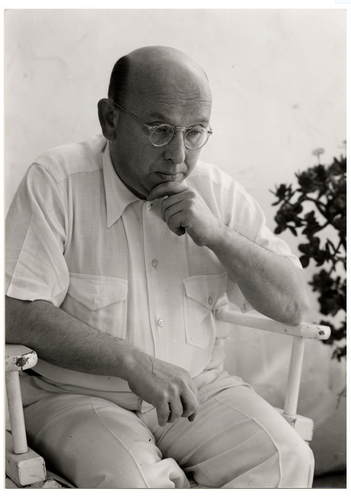

I will conclude with a few more photos from the Arnold Schönberg Center website. I highly recommend this website as it is a wealth of information on Arnold Schoenberg!

Here is the link:

https://www.schoenberg.at/index.php/en/